Leading Blog | Posts by Category |

Leading Blog | Posts by Category |

07.14.23

Why Teaching and Learning Must Be Two-Way

ADDING value and sustaining growth is accomplished by developing others to lead at every level. Simply put, Noel Tichy writes in The Cycle of Leadership, “The company that fields the better team with the smarter people and has them working most often on the things that create the most value will win out over its competitors.” The way this is done is through an interactive teaching/learning process, not a lecture. Great teaching is a two-way street—both become smarter through interaction with each other. It isn’t about alternating roles. You teach me something, and I’ll teach you something. Rather, it is a process of mutual exploration and exchange during which the “teacher” and the “learner” become smarter. Interactive teaching/learning is a critical skill, and it springs from a curious mind. It comes across as freshness and openness on the part of the leader. Executive coach Art Petty leverages this idea in his workshops. He wrote, “Every individual comes to a program with a unique perspective and experiences, and together, we look for common themes and threads we can mine to help all of us.” And Art often shares those insights on his blog. One-way teaching is a natural way of thinking about leadership development. But it limits us as we share only our perspective and often miss the new dynamics that the current reality places on the organization. The hierarchical teacher foregoes the opportunity to grow and learn. Ironically, the more we learn, the less we think we need to know. We become knowers and not learners. But the more we learn, the more we should see the need to explore more and learn more. Leadership is learning at all levels, or it is not leading. When teaching and learning are two-way, we all learn.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 08:57 AM

02.22.21

How to Become a Hyper-Learner

STAYING relevant in this Digital Age requires that we learn, unlearn, and relearn as a way of being. Ed Hess calls it Hyper-Learning. How well we think, learn, and engage in the human tasks of the future depends on how well we manage and optimize what’s going on with our minds, brains, and bodies. Humankind has always faced these challenges but what is different today is the intensity—the timeframe we have available to learn, unlearn, and relearn. Our egos make us think we know more than we do and gets in the way of hyper-learning. Fear, too, is an inhibitor. If we are to be hyper-learn, we need to listen to understand other perspectives. Too often, we listen to argue or to reinforce our point. To become a Hyper-Learner, we need to become our “Best Self cognitively, behaviorally, and emotionally.” This requires three main steps: Step 1: Achieve Inner Peace Inner peace is important because in this state, you are better able to approach things with an open, nonjudgmental, and fearless mind. We cultivate inner peace by quieting our ego, our mind, and our body, and developing a positive emotional state. With inner peace, you are better able to slow down and “exercise choice in your thinking, emotions, and behaviors.” What you must confront is the question of whether your ego is so loud that it impedes your ability to become a Hyper-Learner. “A Quiet Mind is a calm, silent mind focused on the present moment.” It is not competitive. It is a mind that tries to see the world as it is without judging or the distractions that come from multitasking or ruminating. A Quite Body is one that is at peace. “It is not tense, chronically stressed, anxious, angry, fearful, or experiencing pain.” Most of these issues are mental and deal with how we think. They can be influenced by certain meditation and deep breathing practices. Positive emotions are essential to Hyper-Learning. We can learn to generate positive emotions. “Being kind to others, caring about others, being thankful for what you have, and experiencing simple daily joys all contribute to having a Positive Emotional State.” Step 2: Adopt a Hyper-Learning Mindset Hess has indemnified two lifelong learning mindsets: the Growth Mindset and the NewSmart Mindset. Carol Dweck popularized the Growth Mindset. As opposed to the fixed mindset, the growth mindset is based on the idea that our intelligence is not fixed but that we can learn, improve our skills, and grow. It sees potential. The NewSmart Mindset redefines what “smart” is. Rather than seeing smart as knowledge accumulation and recall, NewSmart views smart and thinking in ways computers can’t— “ways that involve exploration, discovery, imagination, morals, creativity, innovation, and critical thinking when there are lots of unknowns or little data.” Step 3: Behave Like a Hyper-Learner As a Hyper-Learner, your behavior matters. “Behaviors are how you operationalize your values, belief, and purpose.” Great line. Behaviors reflect how you see or define yourself. To change behaviors, you have to change the story you tell about yourself. Behaviors are granular. They are reflected in how you talk, your tone, your physical presence, your volume, how you connect with people, how you listen, how you think, how you manage your emotions, how you ask questions, and how you react. Hess asks us to list what behaviors do we think are necessary to become Hyper-Learners? He provides a list of some like curiosity, humility, social intelligence, empathy, courage, resilience, and trustworthiness. We not only need to be different, but we must learn to work differently. Specifically, we need to humanize the workplace and create an environment that mitigates ego and fear. Humanizing the Workplace means that the desired values and behaviors are woven into the daily way of working—the daily fabric of the organization—through practices that are used by all people every day. Hess emphasizes the importance of emotional connections. And the answer to the question, why do I exist? “People are yearning for more from their work. They want more meaning and richness and to experience more joy. They want higher-quality emotional connections with others. And it’s not just coming from younger generations.” What makes Hyper-Learning practical is its focus on behaviors. He does this through explanation but, more importantly, with a workshop/workbook format that encourages active participation with the text through reflection and journaling.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 12:01 AM

06.19.18

Never Stop Learning

W We often think of learning as something we are doing all of the time. But we aren’t. Mostly we are repeating or reinforcing what we already know. And that gets in the way of learning. And when it comes to learning from mistakes we ignore, blame, and rationalize to protect our self-image. All of which, deprive us of the chance to learn. In Never Stop Learning published by Harvard Business Review Press, UNCC professor Bradley Staats provides the processes we need to follow to become perpetual learners. Like most things worthwhile learning must be deliberate. Learning is a process that requires your constant attention. Learning Requires Process Focus, Not Outcome Focus Learners focus on how they got to the result. For me, this was the key chapter. Process focus involves understanding all of the elements that contributed to the outcome. An outcome is not a single event. It is the result of many smaller events. We tend to place more emphasis on the outcome than we should. And perhaps more importantly, “we believe the outcome is a reflection of our finite ability and thus we judge it as an evaluation of ourselves—so we focus on performance goals rather than learning goals, to our detriment.” A focus on learning goals builds on a growth mindset. “To a growth mindset, the outcome is simply one input about the state of the process and the individual’s general learning.” And here’s another benefit of focusing on the process. Dancer and choreographer Martha Graham said, “Freedom to a dancer means discipline. That is what technique is for—liberation.” Staats adds, “Success, even in a novel situation such as dance, depends on understanding the building blocks. Once we understand the basics, we can deviate productively to innovate and learn.” Ask Questions We can’t learn if we think we have all of the answers. “When we ask questions, we fill in the blanks in our own knowledge.” Staats recommends we ask, “Is my approach correct?” Again this gets back to his point on having a process focus. We think our knowledge is more complete than it is and so we miss learning opportunities. Like the tortoise in Aesop’s fable, “we often need to slow down to go fast. Slow and steady, like the tortoise, can win the race when we ask thoughtful questions to help us learn. Rushing to answers when the world is changing around you is a shortsighted strategy at best. The answer that worked yesterday is unlikely to be correct tomorrow. Increasingly, we are tasked with activities that require judgment and expertise—not just mindless repetition of the same answer.” We don’t ask enough questions. Learning Requires Recharging and Reflection, Not Constant Action We always hear that we need to have an action bias. And that’s great in overcoming analysis paralysis and of course, results are the basis of our reputation. But doing for the sake of doing something is worse. Staats relates the example of the strategy of professional goalies when dealing with penalty kicks. Statistically they would be better off staying put in the center to stop the penalty kick. But they most often don’t. Researchers found that most often they don’t. “They wanted to be seen doing something, even if that something was wrong. Given that most tasks that require our attention involve uncertainty, it is inevitable that we will sometimes make the wrong choice…. This fear of making the wrong choice prevents us from pursuing strategies that could help us both now and in the long run.” I would add, who wants to be standing still and miss stopping the kick. We want to be seen as doing something even if statistically, moving might not be the best strategy. The false impression is that we aren’t trying. Being Yourself to Learn When we are ourselves, we will be “more positive, more motivated, and able to engage in more open learning.” Staats notes, “The challenge is to be authentic but not outlandish. The advice holds: you must release the individual if you want to learn. But as with many things, moderation is important. Overdoing it, as defined by the situation you’re in, will create problems for you and others.” Sometimes it’s wise to dial back the authentic you. Playing to Strengths, not fixating on Weaknesses Here’s the key: “Don’t try to fix irrelevant shortcomings. We learn best when we play to our strengths—those capabilities at which we excel.” We all have some critical weaknesses that need our attention. And those should be given our attention. Say no to the idea that any weakness must be treated as a learning need. Instead, focus on the key qualities that enable you to create value and differentiate yourself. And of course, we need to keep our strengths in check. As the Swiss-German philosopher wrote, “All substances are poisons; there is not which is not a poison. The right dose differentiates a poison from a remedy.” Specialization and Variety We can become boxed in by what we know. Only by intentionally expanding our knowledge and experience and including others can we make new connections. “When we become too specialized, we see what we want to believe rather than what is actually there. We think deep specialization is a way to learn, but it may constrain how we understand new material. Learning therefore, must incorporate variety as well as specialization.” Variety keeps us from running on autopilot. We think the world works a certain way. When we encounter new circumstances, “we fail to learn because we believe that the same od lessons apply.” A balance of specialization and variety is important though. “Moving across different domains may permit us to see connections, but only if our understanding is deep enough to recognize them.” Learning from Others The people we interact with are key to our success. Interestingly, Google found that “great team performance, learning, and innovation were less a function of individuals’ prior skills than of how the team members interacted and their previous experience with one another.” Staats has found that, “In isolation I may be able to come up with an interesting way to think about things, but the back-and-forth of having that idea challenged is what tests and thus improves me.” Determination When it comes to learning, it’s easy to get distracted by everything we need to get done. And our environment changes. But if we fail to learn wee become irrelevant. “We end up solving yesterday’s problems too late instead of tackling tomorrow’s problems before someone else does.” Microsoft’s CEO Satya Nadella said, “Ultimately, the ‘learn-it-all’ will always do better than the ‘know-it-all.’” Living in a learning economy means that we must all approach learning with four mindsets: focused (choose which topics to learn and focus on them deeply), fast (get up to speed quickly), frequent (always be open to learning even from the most unexpected places), and flexible (be able to decelerate and switch to the next opportunity).

Posted by Michael McKinney at 06:08 PM

05.15.15

5 Leadership Lessons: How to be More Creative and Enrich Your Life

“Curiosity has been the most valuable quality, the most important resource, the central motivation of my life,” writes Hollywood producer Brian Grazer in A Curious Mind. Early in life, Grazer began having what he calls “curiosity conversations.” He began tracking down people he was curious about and asking them if he could sit down with them and talk. He particularly looked for people outside of the entertainment business. The goal was to learn something. He says, “I want to understand what makes people tick; I want to see if I can connect a person’s attitude and personality with their work, with their challenges and accomplishments.” Grazer is a storyteller by trade and it comes through in the stories he tells of the people he has met through his curiosity conversations. Conversations like these get you out of your head and better connected to reality. They provide great insights into yourself and others. It would be a worthwhile goal for anyone to create similar conversations in their own life. And Grazer persuasively argues that you should. (Give one to a graduate. They’ll get it. I put my son on to the project.) Here are five leadership lessons from A Curious Mind. I particularly like the first point as it provides a starting point—a practical behavior—to develop the thinking and the creativity that drives innovation.

“When curiosity really captures you, it fits the pieces of the world together. You may have to learn about the parts, but when you’re done, you have a picture of something you never understood before.” Grazer encourages us to keep asking questions until something interesting happens! And it can start with anyone you come into contact with. Everyone has a story to tell—go and be surprised.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 07:20 PM

05.08.15

5 Secrets to Learning Better

WITH exam season upon us in the northern hemisphere, experimental psychologist Tom Stafford has offered some lessons for learning better. He and his colleague Mike Dewar, studied how people learn to play an online game. “Computer games provide a great way to study learning: they are something people spend many hours practicing, and they automatically record every action people take as they practice. Players even finish the game with a score that tells them how good they are.” Here is what they found:

Posted by Michael McKinney at 12:06 AM

01.22.15

A Beautiful Constraint

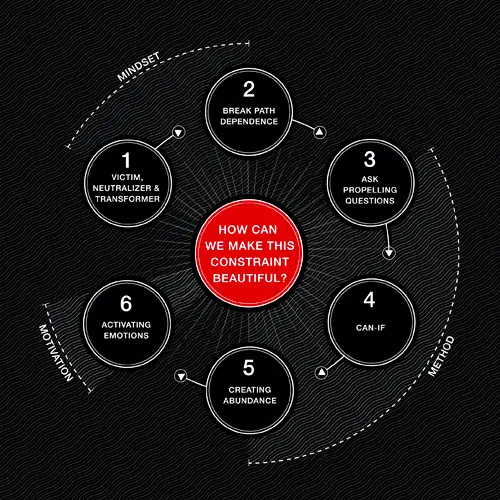

TYPICALLY we look at a constraint as a negative. A problem to be solved. But what if a constraint was the gift that opened up previously unimagined possibilities? What if a constraint was the gift that took you to the next level? Authors Adam Morgan and Mark Barden remind us in A Beautiful Constraint that Google’s home page is as simple as it is because that was the limit of Larry Page’s coding ability at the time. The overall-wearing hero Mario is as colorful as he is because of the challenges of eight-bit technology. And which of us would be using Twitter at all today if it had a limit of 14,000 characters rather than 140? We are all faced with the challenge of growing within the constraints of time, resources, method and /or people. Sometimes constraints are imposed on us and sometimes we benefit by placing constraints on ourselves. “We are living in an era of extraordinary people rewriting our sense of what is possible. They make an unarguable case that a constraint should be regarded as a stimulus for positive change—we can choose to use it as an impetus to explore something new and arrive at a breakthrough. Not in spite of the constraint, but because of it.” Organizations of all types—business, churches and schools—and people from all walks of life would benefit from understanding how to reframe a constraint into a better way of doing something. We begin the process by creating the right mindset. We need to increase our ambition relative to the constraint not to scale back our ambition to satisfy the constraint. That’s victim mentality. And that’s usually where we begin. Better yet, we can try to find a way to neutralize the constraint so we can deliver on our ambition. But the authors have created a path for us to become transformers—to find a way to use a constraint as an opportunity, possibly even increasing our ambition along the way.  Often transformers will impose constraints upon themselves to force themselves to unearth different, possibly transformative strategies and solutions. This helps to reduce path dependence or the assumptions and ways of thinking about solutions that define “the way we do things around here.” “Today’s path is really yesterday’s path.” We must examine all of the ingrained habits that may stand in the way of our being able to see and realize the possibilities in a constraint. To bind our bold ambition to a significant constraint we have to ask a propelling question. The kind of “what if…?” question that forces us to think and behave in a better way. “If we don’t ask propelling questions of ourselves, someone is going to ask them of us, and by that time we will be behind the curve.” To answer a propelling question we need to answer not with a “we can’t because” statement but with a “we can if” statement. It focuses the nature of the conversation on how something could be possible and not on whether it would be possible. Then we get resourceful. What stops us from being more resourceful is the way we think about resources. We tend to think of the resources available to us as the ones within our immediate control. But there are all kinds of resources outside of our immediate control. One method is to create shared agendas. “We, who might appear to have little, need to help them see that we have what they want.” There are organizations that routinely embrace constraints to make themselves better. The beautiful constraint process cannot be managed, it must be led. “When making constraints beautiful, motivation is method. Breakthrough happens when a propelling question meets strong emotions. Without activating the right emotions, it will be too easy to regress to the victim mindset.” The authors note that “if we are heading into a more constrained future, then how we manage those constraints will determine how we progress.” As a leader, steering your organization towards constraints sooner rather than later, is an important source of competitive advantage. Raising the level of ambition alongside a constraint encourages growth and learning—both individually and organizationally—because it causes us to reexamine our current paths, assumptions, and ways of thinking. A Beautiful Constraint is a outstanding book with inspiring examples that will spark your imagination to create your own beautiful constraint. It should be standard issue to every student as the thinking described here will serve them well in life. What constraint will you go and make beautiful?

Posted by Michael McKinney at 10:02 PM

01.16.15

Is What You Know Holding You Back?

INVESTOR and entrepreneur Paul Kedrosky wrote in What Should We Be Worried About? by John Brockman: "Writer William Gibson once famously said that 'The future is already here—it's just not very evenly distributed.' I worry more that the past is here—it's just so evenly distributed that we can't get to the future." What we know has a bearing on what we learn. What we know can not only limit if we learn but it limits what we learn. What we know acts as a filter to what we learn. We naturally filter out things that don’t fit with things we already know. We are quite adept at putting a spin on what we learn so that it is consistent with what we already know. In other words, we may be taking in more information, we may be studying more but we are not learning or doing anything new. We are merely reinforcing what we already believe to be true and ignoring or explaining away that which doesn’t fit with what we know. In what way is old thinking holding you back?

Posted by Michael McKinney at 03:47 PM

01.13.15

There is No Magic in Failing

DESPITE all the talk about making you feel better about inevitable failures, failure is only an opportunity if you learn from it and then act on it. What if you actually orchestrated better failures? Designed useful failures instead of hit or miss failures? That’s what Anjali Sastry and Kara Penn suggest in their book Fail Better. “The right kind of failure instructs, refines, and improves ideas, work products, skills, capacities, and teamwork.” The idea is to “generate small, smart mistakes that enable your team its work requirements (a first-order performance goal) while building capacity, habits, and insight (the second-order, deeper change).”To this end they offer the three-step Fail Better Method: Launch your project. The goal of the launch phase is not to over plan and set things in stone, but to consider your project in context, anticipate outcomes as tied to a series of logical assumptions, pull together your resources, and get the right people involved. Plan your projects in such a way as to make any failures useful. Build and refine. It can be helpful to think of your project as a cauldron for experimentation and learning—in which you will plan, act, and assess to decide the next step. Approach your project in cycles or chunks in which you plan, act, and assess, then take the next step, and even big projects become more tractable while enabling your team to learn and refine its plans. Identify and apply what you've learned. The final step is embedding what you’ve learned not just within your team but organizationally. No one can know exactly why things turn out the way they do. Even while learning from your mistakes, the corrective action is based on incomplete knowledge. You will need to “identify lessons learned while bearing in mind that your understanding is limited.” Learning is a skill that is never taught, but it is a critical one as we go forward. A systems approach is essential. “Systems thinking teaches us that it’s more fruitful to take an endogenous view that seeks to explain how the results are a product of factors in which you play a part as well. You have much more power to shape outcomes if you can better understand how the problems and opportunities you face today are connected to your own past actions and are influenced by the structure of the industry, society, and ecosystem in which you play a role.” Our biggest issues will not be solved with a single solution. Rather they will be solved bit-by-bit—even across groups—one effort at a time. Learning as we go.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 10:23 PM

11.26.14

Learn or Die

OUR ABILITY (and willingness) to learn impacts our personal and business growth, operational excellence, and our capacity to innovate. More than ever, it truly is learn or die. In Learn or Die, Ed Hess writes that learning is impacted by our “reflexive ways of thinking, the rigidity of our mental models, and the strength of our ego defense systems.” So to a large degree is means overcoming our humanness. We prefer to validate what we already know rather than looking at evidence to the contrary. By and large, that’s a function of our ego. “In many cases, learning comes from mistakes or failures or other people disagreeing with us, which that means in order to learn, we often have to admit that we are wrong.” The author admits that “To become a better learner, I had to quiet my ego.” As a result, he also became a better thinker and leader. Negative thinking is toxic to learning. “In order to maximize our learning we have to be sensitive to and manage our emotions.” As a leader, you need to be concerned about the environment of the people you lead. “The litmus test of a learning organization is being receptive to information that goes against the established way and a tolerance for failure and mistakes.” To accomplish this not only should the environment be positive, but people need to be treated with respect, dignity, and trust, mistakes should not be characterized as “personal failures but as the result of bad learning systems or too little effort,” people should also believe that they have some control over their actions, have a sense of self-efficacy and contribution. Hess writes that “The U.S. Army Special Forces believes that adaptability—learning—is predicated on self-efficacy, resiliency, open-mindedness, mastery achievement motivation, and tolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty.” Too often we sabotage our own learning by our need to be right. We need to be able to admit when we are wrong and quite frankly accept the “magnitude of our ignorance.” “Real learning, in most cases, requires us to change what we believe, and humble inquiry [open-mindedness with no predetermined or hidden agenda], helps us do that.” Because we have difficulty seeing ourselves and examining our own assumptions, “learning is a team sport.” If we want to learn, we “must engage in effective learning conversations.” Learning conversations are conversations where we feel safe in disclosing ourselves to others. They bring about a deliberate, nonjudgmental, non-defensive open-minded exchange. We learn from each other.

The culture at Bridgewater may seem extreme to some but there is no doubt that they are serious about growth and learning. As Ray sees it, achieving one’s goals is more likely to occur if one strives to be an independent thinker by learning. That, in turn, requires one to be honest about one’s strengths and weaknesses and to deal directly with one’s weaknesses by accepting them, seeking and being open to feedback and creating workarounds that mitigate one’s weaknesses. At Bridgewater, everyone knows everyone else’s strengths and weaknesses. It’s part of their company-wide feedback loop. It’s based on truth which Ray believes “is the essential foundation for producing good outcomes.” “Searching for the truth and confronting one’s personal weaknesses in a radically transparent environment builds personal relationships.” At Bridgewater they are just as concerned about how one arrives at an answer as they do the answer itself. They encourage people to be independent thinkers. A former Navy SEAL came to work at Bridgewater because he said the two cultures overlapped. “He said both organizations focus on learning, adaptation, recruiting high caliber people, and teaching them to be better thinkers and to relentlessly pursue constant improvement.” Bridgewater has created a series of tools for use in evaluating employees and for employees to manage their personal growth” the Dot Collector and Dot Connector, Issues Log and Issue Log Diagnosis Card, Pain Button and Baseball Card. With the Dot Collector allows anyone to give any other employee performance feedback. The Dot Connector is a database of feedback every employee has received from anyone. The data is grouped according to a list of seventy-seven attributes and then summarized to give each employee a picture of his or her feedback by strengths and weaknesses and by attributes. The Pain Button app is based on Ray’s formula: Pain + Reflection = Progress. “The purpose of the pain app is for one to write down and reflect on the ‘pains’ one is experiencing in order to understand what’s causing them and to deal with those causes effectively.” Ray himself is included in the process and is subject to evaluation by anyone in the company. Frankly, I have never read about an organization with such radical transparency. Hess says that in all of his research of over 100 high-performance companies over the past ten years, Bridgewater is the only business organization he has found that “has squarely faced our ‘humanness.’” Learn or Die is a book everyone who is serious about learning and growth—personally or organizationally—should read. If you thought you were serious about it, Learn or Die will take you to a whole new level with tools, case studies, and insights that will challenge your commitment to learning.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 11:28 AM

08.06.14

How to Accelerate Learning and Change Lives

TEACHERS are the builders of the future. In a book written for teachers, we find a valuable book for all leaders because leaders are teachers. Leaders are educators. In The Best Teacher in You, you will find the thinking and approaches behind highly effective teachers who accelerate learning and change lives. There are two kinds of change that individuals experience: incremental change and deep change. “We frequently make incremental changes: We make adjustments, we elaborate on a practice, we try harder, and we exert a greater degree of control. In other words, we attempt to solve the problem using the assumptions we currently hold. Deep change is more demanding because it requires the surrender of control….It involves embracing purpose and then moving forward by trial and error while attending to real-time feedback.” It is deep change that we seek to bring about as teachers and leaders. There are two views to making this happen: directive and co-creative. A directive perspective suggests the teacher directs and controls the classroom. “Teaching is a process in which a more expert person imparts knowledge or skill to a less expert person.” A directive perspective is a place to begin but when we build on it, we grow into a co-creative perspective and we move beyond direction, control, discipline, and repetition. “As the teacher and the students commit to a common purpose and form high-quality relationships, they become a system that has emergent possibilities. In a co-creative, collaborative environment, students hold each other accountable, leadership is shared, and new perspectives emerge. The teacher/leader becomes a facilitator. In a practical way, the authors—Robert Quinn, Katherine Heynoski, Mike Thomas, and Gretchen Spreitzer—have developed a framework consisting of four themes at the center of highly effective teachers' practice. It incorporates both the directive and co-creative perspectives. Each area of effectiveness is associated with particular skills and preferences and all the quadrants have value. After we identify in which of these areas we can find our individual strengths, we can then accelerate our development when we begin to stretch from a position of strength toward an area of growth. If we are very “red” for example, our effectiveness might improve if we became more “yellow” or “green.” A very helpful concept.

Here are a few ideas presented in the book from highly effective teachers: Developing the desire to learn: “This process does not begin with her acting on the students. It begins with her acting upon herself. She does the internal work necessary to display her own enjoyment of learning…. [Finally the teacher] is no longer the center of attention, and neither are the students. At the center of attention is the process of learning. The class transforms from a hierarchy to an adaptive learning organization.” Structure: “Structure is not his purpose. Structure serves his purpose.” “Structure and control are paths to freedom and learning.” “Structure and routine are there so students can work outside the box.” “I think the more structured and organized I am, the more creative we can be. Without structure it doesn’t work. We need organized chaos. We need some way to manage the mess. Structure and order free me.” Enhancing relationships: Sarah’s “most immediate concern is how to negotiate the rift between the content she must teach and the real-life experiences of her students.” Students are often “passive observers of their education because the directive perspective is taken too far. She feels that overly directive teaching can minimize the emotional content of the curriculum. Rather than tell her students what is right or wrong, she wants them to engage and ‘negotiate’ difficult social issues so that they come to their own deep understanding of what is right and wrong.”

Posted by Michael McKinney at 09:08 AM

01.15.14

Leading Views: Pervasive Learning

Success in leadership is not about what you know but the knowledge you can access. We need to focus on continuous learning or what Pontefract calls Pervasive Learning: The switch from a “training is an event” fixed mindset to “learning is a collaborative, continuous, connected and community-based” growth mindset. The skills we need now are reflected in this statement from British Columbia’s Ministry of Education: [The current curriculum] tends to focus on teaching children factual content rather than concepts and processes – emphasizing what they learn over how they learn, which is exactly the opposite of what modern education should strive to do. In today’s technology-enabled world, students have virtually instant access to a limitless amount of information. The greater value of education for every student is not in learning the information but in learning the skills they need to successfully find, consume, think about and apply it in their lives.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 11:14 PM

01.03.14

How do Leaders Gain Deep Insights?Reality and truth and hard for leaders to come by—especially if they think they are the repository of all truth. Leaders can easily get swept up in the “truth” perpetuated by the faithful that surround them.Like in Han Christian Anderson’s story, naked kings parade before followers too insecure and fearful to tell them they have no clothes on. These naked kings begin to believe that the world is a fixed landscape that they only truly understand. Nigel Nicholson believes a way out is Management By Wandering Around. He writes in The “I” of Leadership, that “leaders need ways of getting under the wire; to penetrate the defenses and illusions that thickly sprout around all the interstices of power in organizations.” Napoleon sleeping, wrapped in a blanket on the battlefield alongside his men; Gates inviting emails from the ranks of his global Microsoft empire; company patriarch Raymond Ackerman continually touring the stores of his South African Pick-n-Pay grocery chain; and numerous hands-on business leaders the world over walking the job in an unscheduled, intimate manner, chatting to their people. Gaining insight means: Getting out and talking to people you don’t normally rely on for information. For better or worse, Nicholson explains that people tell their leaders what they want to hear in order to be thought of well, to keep them confident in their own beliefs and out of the fear to remain on the winning side. Unfortunately, while this keeps the leader comfortable and warm, it also makes them delusional. The leader must break organizational designs that conspire to “separate leaders from their people and the truths they have to tell.” Gaining insight means cultivating quality feedback. Of course, all of this makes the issue of humility that much more difficult. Without humility we can’t learn and become stuck in a cycle of repeating the same thinking and patterns of behavior we always have—often to our own detriment. Nicholson writes, “the best bosses teach their people that they really do love the truth and are not afraid of it, even when it may reflect badly on them, but many doubletalk, like the remark of the legendary movie mogul, Sam Goldwyn, who reputedly said:” I don’t want yes men around me. I want people to tell me the truth, even if it costs them their jobs.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 01:12 PM

01.08.13

Antifragile or How We Become Fragile

IN Antifragile, Nassim Nicholas Taleb reports on things that are fragile and things that are antifragile and how they became that way. Taleb says antifragile isn’t resilience given his narrow definition of it. It’s more. Resilience survives. Things that are antifragile don’t just survive, they get better with random event and shocks. The opposite is fragile. Though often unintentionally, we tend to make things fragile. We have been fragilizing the economy, our health, political life, education, almost everything … by suppressing randomness and volatility. … Complex systems are weakened, even killed, when deprived of stressors. Much of our modern, structured, world has been harming us with top-down policies and contraptions which do precisely this: an insult to the anitifragility of systems. By trying to make things simple and linear we run the risk of underestimating randomness and its role in everything. And more importantly, we fail then to benefit from them. Thus while we may be resilient or robust, we are not antifragile. “You only get a measure of order and control when you embrace randomness,” says Taleb. Our character should be antifragile. Random events should serve to make you better than before. Rules are fragile. Principles are resilient. Virtue is antifragile. Classroom learning is fragile. Real-life and experiential knowledge are resilient. Real-life and a library are antifragile. Success actually makes us fragile. We need to be antifragile to survive it. “When you are fragile, you depend on things following the exact planned course, with as little deviation as possible—for deviations are more harmful than helpful.” Mistakes and successes—especially those of others—give us a lot of information. If we can learn from them, they can make us antifragile. Taleb writes: My characterization of a loser is someone who, after making a mistake, doesn’t introspect, doesn’t exploit it, feels embarrassed and defensive rather than enriched with a new piece of information, and tries to explain why he made the mistake rather than moving on. These types often consider themselves the “victims” of some large plot, a bad boss, or bad weather. Randomness is not a bad thing. We make our organizations fragile when we are overprotective; when we try to iron out all of the variations and wrinkles that are a part of life. The longer we go without randomness, without variations, without setbacks, the worse the consequences when the unpredictable occurs. “Preventing noise makes the problem worse in the long run.” Yet we still think we benefit from protecting people and organizations from volatility—from life. It’s a practice with unintended yet harmful side effects. A fact of life: “no stability without volatility.” A little confusion can lead to teachable moments, growth and stability. Antifragile is an interesting and at times entertaining read. Taleb borrows from all disciplines to explain “how to live in a world we don’t understand or, rather, how not to be afraid to work with things we patently don’t understand, and, more principally, in what manner we should work with these.”

Posted by Michael McKinney at 10:00 PM

04.20.12

Restoring Your Ability to Choose

WE all like to think we are in charge of our choices. But the fact is that most of the time we are reacting, not choosing. Most of what we label choice is habit. We’re really on automatic. It can even lead us to think that we have no choice. Only when we pause—slow-down to think and reflect—are we exercising our ability to choose. Nance Guilmartin writes in The Power of Pause that a pause is “any space between an action and your reaction.” And it’s vitally important:Today you need the ability to discern what lies beneath people’s words, their reactions, or their silence. If you don’t build the neuropathways in your brain to pause, to momentarily disengage your automatic reactions, you can trigger a chain reaction that derails your best intentions and strategies. Guilmartin lists seven cues that a pause is in your best interest. It’s time to pause if you are thinking, feeling, or saying:

The Power of Pause Method is based on a three-step Effectiveness Equation and twelve Power of Pause practices. The equation: Professional Effectiveness and Personal Fulfillment Not surprisingly, the equation references an all-important addend, humility. Humility should fuel your curiosity and drive the need to pause. Guilmartin explains that “in situations where you think you know enough, pausing to wonder what you don’t know is a vital, even game-changing leadership skill.” The twelve practices are:

Posted by Michael McKinney at 04:36 PM

02.07.11

Consider: Harnessing the Power of Reflective Thinking in Your Organization

PETER SENGE, founder of the Society of Organizational Learning and senior lecturer at the MIT Sloan School of Management, once observed, “Most managers do not reflect carefully on their actions.” Most managers are too busy “running” to reflect. While reflection seems to have no place in a competitive business environment, it is where meaning is created, behaviors are regulated, values are refined, assumptions are challenged, intuition is accessed, and where we learn about who we are. Some of the greatest barriers to getting the results we want lie within us. Growth happens when we stop repeating our habitual patterns and behaviors and begin to see things in a new way and in the process, discover the power to create the results we want. That makes Consider: Harnessing the Power of Reflective Thinking in Your Organization, one of the most important books you’ll read this year. Author Daniel Patrick Forrester states, “Stepping away from the problem—and structuring time to think and reflect—just may prove the most powerful differentiator that allows your organization to remain relevant and survive…. The best decisions, insights, ideas, and outcomes result when we take sufficient time to think and reflect….Only by carving out think time and reflection can we actually understand, in an entirely different context, the actions we take.”He defines think time as “the purposeful elevation of chunks of our work time, forged within densely packed schedules. It forces the consideration of core significant and pending decisions, outside of cursory overviews and immediate response…. Reflection is the deliberate act of stepping back from daily habits and routines (without looming and immediate deadline pressures), either alone or within small and sequestered groups. It’s where meaning is derived through reconsideration of fundamental assumptions, the efficacy of past decisions and the consequences including the downside of future actions. It’s where space is given for the ‘totally unexpected’ to emerge.” Even if we can agree on the value of think time, we still regard it as a luxury. There’s just no time. But what emerges from Forrester’s research is the fact that we can’t afford not to. It is at the core of what allows a business to thrive. It’s what we don’t know that has a disproportionate impact on us personally and organizationally. We don’t really see the reality we face. Reflection in effect expands our perspectives and thus reveals to us more options and that gets to the heart of what leadership is all about. The point is to make the unseen seen so we can act on it. Forrester interviewed Sarah Sewall who worked with General Petraeus and others to rewrite the military’s counterinsurgency doctrine. Sewall noted, “We are now in a world of increasing specialization, where people get narrower and narrower in their viewpoints in order to become more expert and ‘useful.’ My view is that people become more myopic in how they can think about problems and solutions. We wind up shuttered in our ability to think about possibilities.” This tendency is best counteracted by think time and reflection; being able to back away and incorporate more and varied thinking. Forrester asks, “What is the last document or strategy you can point to as a ‘product of reflection’ built with all parts of the organization and senior-level involvement? If you can’t cite one, it may indicate a culture that values immediacy and the short term over reflection and scalable problem-solving.” Recognizing the need for reflection and actually doing it are two different things. Reflection is a discipline. General Petraeus told Forrester that “he forces bursts of reflection into his day, where he pauses to read, think, and then moves to the next iteration—recognizing that thoughtful insights are not born through real-time analysis.” Forrester suggests that we set time aside for a meeting with oneself. “It isn’t hard to book a meeting with yourself, when you are off-limits to everything but your thoughts.” He notes too, “The power of reflection lies not in how much time we allocate to it. The power of reflection lies in how we choose to use that time and what structure we bring to the fleeting disjointed moments we are afforded.” While some situations required his immediate action, Forrester describes how Lincoln “developed ways to force time to think (if even only for a few minutes) before acting. Even Lincoln had to resist the “instantaneous nature of the telegraph.” Some organizations he has studied have adopted a no internal e-mail Friday policy and other ways to temporarily disconnect from technology. Although these ideas may not work for you, the point is made so that you might consider the impact these technologies are having on the productivity and well-being of your staff. There is always one more e-mail and it will control you if you let it. “When overworked people declare that they ‘just don’t have time to think,’ leaders have a choice: They settle for the status quo and declare that it’s the best way the world works today, or they can insist that reflection is a strategic business enabler,” says Forrester. As an organization, you can either educate for it, make it an expectation—a cultural norm—or treat it as a “do it on your own time” activity and pay the price. Leaders need to understand and demonstrate by example that reflection—taking time to consider—is not wasted time. Reflection is the first step in coming to understand how we are connected to our outcomes. Until we see the relationship between the two, we cannot make deep, lasting change and bring thoughtful behaviors to bear on the situations we find ourselves in. Our thinking creates our reality. If we do not reflect on our thinking we stand to miss our connection to the whole. Consider offers a way to break the pattern of continuous partial attention that seems to be our default position in this technological age. It helps to disrupt the habitual thinking that drowns out the reflective, critical thinking we need to become fully present and effective. Consider isn’t a fad. It is the bedrock of successful leadership and living. Upcoming: I asked some leading minds about the discipline of reflection. So, for the rest of the week, I’ll share their thoughts on this important topic. Look for valuable insights from John Kotter, Mark Sanborn, Brian Orchard, Marshall Goldsmith, John Baldoni, Tom Asacker, James Strock, and Jeremy Hunter.  More in this Series:

Posted by Michael McKinney at 01:57 PM

10.15.10

You Already Know How to Be Great

ONE OF the hardest things we will attempt to do is to act on what we already know to do. It’s that difficulty that lies behind much of our search for the next big thing; some way to get around or make easier that which we know we should be doing. It is never easy, but by applying some new thinking, we can get out of our own way. Alan Fine states in You Already Know How to Be Great, that performance improvement is most often an issue of reducing the interference that’s getting in the way of using the knowledge we already have. Fine says that we have to get right the three elements that facilitate the use of the knowledge we already have. They are: Faith: Our beliefs about ourselves and our beliefs about others. High performance is more likely when we believe that we can learn and do better. The absence of Faith could be described as insecurity. Fire: Our energy, passion, motivation, and commitment. High performance is more likely when we are excited about learning and doing. The absence of Fire could be described as indifference. Focus: What we pay attention to and how we pay attention to it. High performance is more likely when we pay attention in a way that will quiet our minds. The absence of Focus could be described as inconsistency. High performance happens when we “get rid of the interference that blocks these natural, inherent human gifts.” Focus is the most powerful tool for removing distractions and, thus, the “most effective way to release Faith and Fire.” If we “create a singular focus on one or more critical variables of the task, we’re far more likely to create the flow state that creates high performance.” More than instructing, Fine believes we would be better off looking to what is blocking Faith, Fire, and Focus in our organizations, performers, families, and teams. Unleashing these qualities facilitates the use of knowledge. As managers, leaders, coaches, or parents, we’re incredulous to think (or more likely, it never even occurs to us to think) that without our excessive instructing, regulating, controlling, directing, and intervening, people might actually be able to perform with greater confidence, more enthusiasm, and more effective focus. Fine introduces the GROW process as a way of creating focus. The process asks: “What is my Goal? What’s the Reality? What are my Options? What’s the best Way Forward? GROW increases Decision Velocity [the speed and accuracy with which we make decisions]. It helps reduce interference, clarify thinking, identify options, and chunk down the challenge into doable tasks. It unblocks Faith, Fire, and Focus and frees people to use the Knowledge they already have. As leaders, we tend to approach most situations by providing more information. We actually nourish the expectation that we are to be telling people what to do when we really need to be working to help them get what’s inside of them out. Fine calls this inside-out coaching. It’s less about providing more Knowledge and more about releasing the Faith, Fire, and Focus that's already there in the performer. It’s more Focus coaching than it is Knowledge coaching. “It’s easy for coaches to get blindsided by what they think people have to pay attention to—to get so focused on the task that they miss the window through which a person can actually pay attention.” “When leaders simply tell people what to do (which is often the case), the result is often a lack of engagement and accountability on the part of the employee and little or no performance improvement. One of the primary observable signs of an outside-in approach is people constantly asking managers, leaders, teachers, or parents what to do.” As a coach, the biggest challenge isn’t the performer; it’s your own interference. You Already Know How to Be Great is about coaching ourselves and others to remove the interference that is blocking performance. It is full of applications of inside-out coaching and the GROW process he advocates. As such, it is an indispensable book for coaches or leaders of all types.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 06:57 PM

09.20.10

Do You Argue With Reality?

CHRIS THURMAN wrote in The Lies We Believe, “The number one cause of our unhappiness are the lies we believe in life.” Too often, we operate apart from reality. Given a choice between reality and our version of it, we are inclined to choose the latter. It is a central tendency of human beings. The result is drama, not peace. “Instead of getting the results we want,” says Cy Wakeman, “we end up with reasons, stories, and excuses for why things didn’t work out—leading to more drama, disengagement, judgment, and ineffective leadership.” In Reality-Based Leadership, Wakeman presents a much-needed wake-up call. We can ditch the drama by getting in touch with what is. Quit making up stories. Quit arguing with reality. Ditching the stories that are causing us stress. “We all tell ourselves stories and live with the resulting drama.” It sounds like:“I shouldn’t have to do this—it’s not part of my job description.

“You are arguing with reality whenever you judge your situation in terms of right and wrong instead of fearlessly confronting what is.” You need to respond to the facts, not the story you create about the facts. This is easier said than done. Interwoven in our stories are our egos, insecurities, and identities. (At one point Wakeman suggests we ask, “Who am I as a manager or as an employee when I believe this story?”) We like our stories. They make us look better. They place the blame somewhere south of us. If other people are always coming up short in our stories, then it’s all about us. But letting go of our stories is not always easy as we have a lot invested in them. Too often our criticism is about setting us apart from others and not about helping them. It says a lot more about us than it does those it is directed towards. Wakeman says, “When you are judging you are not leading.” In her analysis of the case study about Steve and a team he dreaded working with, she concludes, “his biggest obstacle is his belief that they are a negative group. What if he just dropped that whole story and simply responded to reality directly? The phone rings? Answer it. The team ask a question? Answer it, or teach them where to find the answer. The team share what worked in the past? Listen and lead them into the future. The team requests some time with the leader? Engage with them—lead! When Steve began to lead the team rather than judge and criticize, the team began to change for the better.” She adds, “When you focus your energy on what you are able to give And create rather than what you receive, you are truly serving.” Do you see any applications in what you and involved in? Wakeman insightfully writes: “What is missing from a situation is that which you are not giving.” Operating out of a judging mindset of “I know” or “I am right” effectively shuts down the potential to learn or accomplish anything. Moving on based in reality requires setting the story aside and asking, “If I set the story aside, what would I do to help?” The minute you start judging is the very minute you quit leading, serving and adding value. When you’re in judgment, you are dealing with your story—not with reality. Wakeman suggests that when you get off-track:

What stories are you telling yourself that cause you to operate in your own world? While it may be cognitively economical, it is costing you far more in every other area.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 03:54 PM

09.15.10

Timeless Advice from a Father to a Daughter

The Man Who Sold America by Jeffrey Cruikshank and Arthur Schiltz was for me, hard to put down. It is the retelling of the inspiring and remarkable life of Albert Lasker (1880-1952). Lasker has been called the “father of modern advertising.” He had an eye for talent and worked with them to transform the advertising agency from mere brokers to a creative force to build businesses. He developed “reason why” advertising—salesmanship in print. He made Palmolive and Pepsodent household names and invented the "Sun-Maid" and "Sunkist" brands. He made millions for Quaker Oats, Goodyear, Frigidaire, Lucky Strike and Kimberly-Clark and in the process made millions for himself. He advanced millions to friends during the Depression (most of the loans were never repaid) and when prudent, loaned money to clients to finance their advertising campaigns. Lasker was a major investor in the Chicago Cubs. He persuaded William Wrigley to join him in investing in the team. To help the chewing-gum magnate sell more product he pushed to change the name of Cubs Park to Wrigley Field.  Aided by his personal relationship with many leading businesspeople he “applied the insights he gained in one context to give advice in others.” The legendary David Sarnoff of RCA said of him, “Give him an equal knowledge of the facts and I’d rather have his judgment than anybody else I know.” On October 29, 1935, his daughter Mary came to work for him at Lord & Thomas. He left a note on her desk on her first day of work: My darling Mary,Just One More: In 1938, Lord & Thomas hired the obscure comedian Bob Hope to pitch Pepsodent on the radio. Although Lasker enjoyed making and consorting with the stars—and in one case, marrying them—he remained largely unimpressed with them. One day, the head of Lord & Thomas’ broadcast department reported to Lasker that Hope was grumbling about his contract with the agency. “Mr. Lasker,” the subordinate said, “Bob is very unhappy. He says he just can’t put the show together for $4000 a week. He must have $6,000.” “Just between us,” Lasker replied dryly, “I’d rather have Mr. Hope unhappy at $4000 than unhappy at $6,000.”

Posted by Michael McKinney at 09:16 AM

07.07.10

How Many Surface Areas Do You Have? HOW MANY points of contact do you have with the world around you? If we limit ourselves to one area or experience, then we limit our exposure and growth. If we depend too much on one facet of our lives, we isolate ourselves from the world around us and we end up missing what is really going on.

HOW MANY points of contact do you have with the world around you? If we limit ourselves to one area or experience, then we limit our exposure and growth. If we depend too much on one facet of our lives, we isolate ourselves from the world around us and we end up missing what is really going on.

In The Power of Pull the authors share their conversation with entrepreneur Jack Hidary. He explains that people overlook obvious situations because they “paint themselves into a corner such that their entire interaction with the outside world is mediated through this one facet. Then they’re unable to critically analyze where they are. That’s how they end up going down with the ship.” This is important because as authors John Hagel III, John Seely Brown, and Lang Davison point out, “If we are going to succeed in this rapidly changing world, we face two challenges: making sense of the changes around us, and making progress in an increasingly unfamiliar world.” To do this we need to approach what we do in a way that allows us to be in the flow of knowledge and open to serendipitous events that inform us of things we didn’t know and didn’t even know we were looking for. That approach they call pull: the ability to draw out people and resources to address opportunities and challenges. It’s different than push. Push predetermines our needs and then creates systems and standardized processes designed to provide what we need when we need it. It says, “I know better than you. Do this, not that.” It says, “I know. Here’s what you do.” On the other hand, pull says, “I don’t know. I’ll seek.” The pull approach works to help us to find and access people and resources when we need them, the ability to attract people and resources that are relevant and valuable and then to pull from ourselves the insight and performance required to achieve our potential. The attract aspect of pull is critical. In a world that is changing so quickly, we often don’t even know what we are looking for or the questions to ask to get there. It calls for a different approach. It increasingly depends upon serendipity. You need to increase your surface areas. You need to look for ways to pull people and their knowledge toward you. “If you want to find out what it is you don’t know that you don’t know, you need to hang out with other people who might already know it.” We need serendipitous encounters with people because of the importance of the ideas that these people carry with them and the connections they have. People carry tacit knowledge. … You’ve got to stand next to someone who already knows and learn by doing. Tacit knowledge exists only in people’s heads. As edges arise ever more quickly, all of us must not only find the people who carry the new knowledge but get to know them well enough (and provide them with sufficient reciprocal value) that they’re comfortable trying to share it with us. The authors claim that serendipity in certain respects can be shaped. Of course luck is involved, but we can materially affect it by our actions. We need amplifiers and filters. Amplifiers “that can help us reach and connect to large groups of people around the globe that we do not know.” Filters “that can help us to increase the quality as well as the number of unexpected encounters and ensuing relationships that are truly the most relevant and valuable.” We can manage serendipity by:

The authors ask: What are the five places in the world that would offer the richest opportunities for serendipitous encounters with people who share your passions and interests? What actions could you take to increase the likelihood and quality of serendipitous encounters in the online social networks you participate in? Of the people you met serendipitously in any venue over the past year, how many of these people have you actually engaged in some joint initiative related to your passions and interests?

Posted by Michael McKinney at 08:58 AM

06.29.10

Multipliers: How the Best Leaders Make Everyone Smarter

MUCH OF WHAT constitutes good leadership can be summarized in two words: respect and selflessness. How we relate to those two words will determine how we lead. Consider two assumptions that lie at the opposite ends of the spectrum: • Really intelligent people are a rare breed and I am one of the few really smart people. People will never be able to figure things out without me. I need to have all the answers. • Smart people are everywhere and will figure things out and get even smarter in the process. My job is to ask the right questions. What you believe has a big impact on the performance, engagement, loyalty and the transparency you find with those you lead and interact with. In Multipliers: How the Best Leaders Make Everyone Smarter, authors Liz Wiseman and Greg McKeown refer to those with the mindset represented by the first assumption as Diminshers and those with the mindset represented by the second assumption as Multipliers. It explains why some leaders create intelligence around them, while others diminish it. The value of Multipliers is that is shows what these assumptions about people look like in practice and how they are reflected in your behavior. How would you approach your job differently if you believed that people are smart and can figure it out? With a Multiplier mindset, people will surprise you. They will give more. You will learn more. What kind of solutions could we generate if you could access the underutilized brainpower in the world? How much more could you accomplish? It’s not that Diminishers don’t get things done. They do. It’s just that the people around them feel drained, overworked and underutilized. Some leaders seem to drain the “intelligence and capability out of the people around them. Their focus on their own intelligence and their resolve to be the smartest person in the room [has] a diminishing effect on everyone else. For them to look smart, other people had to end up looking dumb.” In short, Diminishers are absorbed in their own intelligence, stifle others, and deplete the organization of crucial intelligence and capability. Multipliers get more done by leveraging (using more) of the intelligence and capabilities of the people around them. They respect others. “Multipliers are leaders who look beyond their own genius and focus their energy on extracting and extending the genius of others.” These are not “feel good” leaders. “They are tough and exacting managers who see a lot of capacity in others and want to utilize that potential to the fullest.” The authors have identified five key behaviors or disciplines that distinguish Multipliers from Diminishers. You are not either/or but are somewhere along a continuum. These are all learned behaviors and have everything to do with how you view people. We don’t have to be great in all disciplines to be a Multiplier, but we have to be at least neutral in those disciplines we struggle with.

They have developed an assessment tool you can use to see where you are. Importantly, the first place to begin is with your assumptions about people. If you don’t have that straight the rest is just manipulation. As with most behaviors, we do them because we feel we have to. They are self-perpetuating. We jump in where we shouldn’t and come to the rescue. Under our “help” (domination) people hold back thereby reaffirming our belief that they just couldn’t do it without us. And they can’t or rather won’t. Instead they quit while still working for us or move on. We see this in ourselves, in others and in organizations of all types. Leaders are especially prone to run over people, because after all, they have the vision, the know-how and the desire to get it done. We have to slow down and remember that we are not there just to get the job done, but to develop others to get the job done. They can (and need to be able to) do it without us. It’s our job to show them how. In many ways, as leaders, we can become accidental Diminishers. The skills that got us into a position of leadership, are not the same skills we need to lead. Leadership requires a shift in our thinking. Wiseman and McKeown write, “Most of the Diminishers had grown up praised for their personal intelligence and had moved up the management ranks on account of personal—and often intellectual—merit. When they become ‘the boss,’ they assumed it was their job to be the smartest and to manage a set of ‘subordinates.’" Here are some thoughts—out of context—from the book that will get you thinking: “Marguerite is so capable she could do virtually any aspect of girl’s camp herself.” But what is interesting about Marguerite isn’t that she could—it is that she doesn’t. Instead, she leads like a Multiplier, invoking brilliance and dedication in the other fifty-nine leaders who make this camp a reality. One leader had a sign on her door: “Ignore me as needed to get your job done.” She told new staff members, “Yes, there will be a few times when I get agitated because I would have done it differently, but I’ll get over it. I’d rather you trust your judgment, keep moving, and get the job done.” The path of least resistance for most smart, driven leaders is to become a Tyrant. Even Michael said, “it’s not like it isn’t tempting to be tyrannical when you can.” Policies—established to create order—often unintentionally keep people from thinking. At best, these policies limit intellectual range of motion as they straitjacket the thinking of the followers. At worst these systems shut down thinking entirely. “It is just easier to hold back and let Kate do the thinking.” [They resign: “Whatever!”] It is a small victory to create space for others to contribute. But it is a huge victory to maintain that space and resist the temptation to jump back in and consume it yourself. An unsafe environment yields only the safest ideas. [Multipliers] ask questions so immense that people can’t answer them based on their current knowledge or where they currently stand. To answer these questions, the organization must learn. His greatest value was not his intelligence, but how he invested his intelligence in others.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 04:28 PM

02.03.10

The Right Fight

IF YOU believe that the single most important thing leaders have to get right is alignment, if you think that the leader’s time is best spent promoting teamwork and making sure everyone is on the same page and playing nice, then you might want to take a look at Saj-Nicole Joni and Damon Beyer’s book, The Right Fight. The book is based on a counterintuitive premise: In an environment where alignment is the only goal, alignment robs us of necessary dissent, of the checks and balances that mitigate risk, and of the tensions that create innovation and sustainable value. In short, you need to systematically orchestrate the right fights but … you need to fight them right. The Right Fight principle is based on the idea that you learn and grow by the right amount of friction and stress. “A certain amount of healthy struggle is good for organizations and for individuals. Indeed, people and organizations perform optimally when they are under the right kinds and amounts of stress.” They add, “With alignment and properly managed tension, organizations hit a sweet spot and start realizing their potential.” Citing a study by Theresa Wellbourne of eePulse, the single greatest predictor of poor performance is when employees are happy or complacent and thus unmotivated to change. The second greatest predictor is when employees are overwhelmed. Both groups exhibit a low level of energy. They conclude that “Tension in the right measure creates the emotional energy people need to change.” The trick for leaders is to avoid these extremes. “Knowing where and when to use tension is critical. Knowing how to work through the tension is equally important.” They lay out three principles that identify right fights and three more principles that clarify the rules of engagement. The first three Right Fight Principles will help you in identifying and eliminating destructive tensions: Right Fight Principle #1: Make it Worth Fighting About. Make it Material. “A right fight has to create significant value, require integration of multiple perspectives, and change the way work gets done in an organization. In short, a material fight is worth the trouble.” Right Fight Principle #2: Focus in the Future, Not the Past. “Obsession with past performance, or intense interest in decisions made months or even years before, is a dead giveaway that your organization is stuck in a wrong fight.” Right Fight Principle #3: Pursue a Noble Purpose. “Right fights connect people with a sense of purpose that goes beyond their own self-interest, unleashing profound collective abilities to create in ways they didn’t think possible.” The final Right Fight Principles guide you in fighting right fights right: Right Fight Principle #4: Make it Sport, Not War. “Right fights, like sports, have to have rules. One of the key tasks for leadership in a right fight is to define the parameters so everyone involved understands how to participate and what it takes to win.” Right Fight Principle #5: Structure Formally but Work Informally. “You need to structure right fights through the ‘formal organization,’ but work out the tensions created by those fights through the ‘informal organization.’” Right Fight Principle #6: Turn Pain into Gain. “There is a fine line between productive tension and destructive distress, and no two people draw that line in exactly the same place. For right fights to be fought right, leaders need to make sure no one is put under unbearable pressure. Turning pain into gain requires leaders to relate to their team members as individuals and to figure out what creates synergy, stretches skills, and honors outcomes for each of them.” There are case studies to illustrate each of these principles in action. It’s easy to see the negative side of tension: focusing on the past, stigmatizing the losers, fighting over turf. “But without tension, nothing moves.” Tension creates an opportunity for leaders to help their organizations fight the right fight.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 08:57 AM

12.17.09

Teaching, Like Leadership, is a Labor of Love

MUCH of what we do everyday involves some kind of teaching—conveying information to others. We can be enlightened by the discussions from the educational arena on what it means to teach and how people learn. Teaching done right is really a labor of love. It’s having a mind oriented toward the future; seeing a bigger picture beyond what is actually being taught in the present.  Magill says that the faculty at the Laboratory Schools are carefully chosen not just for their expertise but “because of their character and because they believe that education can make a difference in how human beings treat each other.” This summer I read a very interesting article with the title “Higher Education Is Stuck In the Middle Ages–Will Universities Adapt or Die Off in Our Digital World?” Its premise is that universities are losing their monopoly on higher learning to the world-wide-web, as the Internet has suddenly become the global platform for the exchange of knowledge between people. Listen to this quote: The old-style lecture, with the professor standing at the podium in front of a large group of students, is still a fixture of university life on many campuses. It’s a model that is teacher-focused, one-way, one-size-fits-all, and the student is isolated in the learning process. Yet the students, who have grown up in an interactive digital world, learn differently. Schooled on Google and Wikipedia, they want to inquire, not rely on the professor for a detailed roadmap. They want an animated conversation, not a lecture. They want an interactive education, not a broadcast one that might have been perfectly fine for the Industrial Age or even for boomers. These students are making new demands of universities, and if the universities try to ignore them, they will do so at their peril. Just as some Universities may be at peril, I know that pre-collegiate education is in trouble at many schools, both public and private. With discovery, creativity, and well-roundedness being pushed to the background while measuring success through federal and state testing programs remains politically popular, it is not surprising that both home instruction and on-line programs keep growing at exponential rates. The structure of a Laboratory Schools’ education, from nursery through high school, demands thinking and learning for all, as opposed to it being an option for only the self-motivated. Do + Think = Learn was from the beginning, is today, and must in the future be our main thing. This coming Saturday, our youngest daughter is getting married in Denver, Colorado. …During the time that I was preparing these remarks, I was also thinking ahead to her wedding and what advice I might give her. … Ironically, I found some parallels with the institution of marriage and this wonderful profession that we chose and would like to practice what I intend to say to her by sharing a few nuggets of wisdom with you. 1. Marriage is not just between two people. Inheriting your spouse’s family is part of the deal. Likewise, working with someone else’s children is not an isolated act. It is done under scrutiny, loving and otherwise, and as a member of a much larger community. 2. Marriage partners need to know, show, and grow their core values. Likewise, we need to remind ourselves why we chose this profession, be able to express what is at the core of our school’s experience, and reject complacency as we become more experienced. It is those core values, not your new home nor our buildings that, in the end, will matter the most. 3. Marriages that last and stay happy are those in which the partners keep falling in love at least once a year. Likewise, our best work occurs when we keep immersing ourselves and falling in love with what we do. So, on this first day of the 2009-2010 school year, renew your vows, and may you once again fall in love.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 09:43 AM

12.16.09

What Prevents Me from Learning Here and Now?

COULD WE be looking at success and failure in the wrong way? Fritz Roethlisberger, former professor at Harvard Business School and author of Man-In-Organization (1968), found that students that were preoccupied with success or failure couldn’t concentrate on their studies. The common thread he found in the cases is that they all viewed success and failure as an either-or proposition; either their project was a success, or it was a failure. Roethlisberger called it a false dichotomy.  A preoccupation with success in the future, says Roethlisberger, makes it difficult to relate to the present. You end up asking the wrong question: “What is the secret of success?” Instead, they should be asking, “what prevents me from learning here and now?” When we are overly preoccupied with the future, we miss the present, where learning and growth take place. We need to stop viewing the present as the means and the future as the end. The future is really just another present when it comes and a new opportunity to learn. If we treat the present as nothing until we achieve success, we miss the significance of the present. To ask “am I a success or a failure” is a silly question, argues Roethlisberger. We are all both a success and a failure. The question is, “What are we learning in our present situation?”

Posted by Michael McKinney at 11:52 AM

05.08.09

Your Acknowledgment List

I WANT TO to draw your attention to two closely related posts by Rick Smith. They address two important issues. First, the need to get good, solid support and feedback, and second, the importance of appreciation. Here are some of the key points he shared: Earlier in my career, I was an executive recruiter, and what always struck me is just how lonely these men and women were. Not Tom Hanks on a desert island lonely – these people were surrounded by people clamoring for their attention. Rather, they were lonely in the sense that they rarely if ever could find a safe place to collaborate with peers around real problems. Their superiors were always looking for the answers, their subordinates were looking for direction. When they were able to interact with those outside of their companies, it was almost always at functions for their industry (i.e. their competitors). Everywhere these executives go, that have to present themselves as if they know the answers, as if they are supremely confident. But guess what? Even the most heralded execs share the same uncertainties as the rest of us. They just aren’t allowed to show it.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 10:31 AM

12.04.08

What is the Secret of Great Performers?