|

| ||||||||||||||||

|

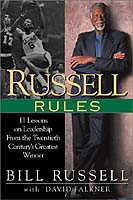

Russell Rules : 11 Lessons on Leadership from the Twentieth Century's Greatest WinnerBill Russell with David Falkner

Excerpt from Russell Rules: 11 Lessons on Leadership from the Twentieth Century's Greatest Winner Lesson Six: Craftsmanship CRAFTSMANSHIP IS ANOTHER WORD FOR QUALITY. IT IS also about getting the best results from your work effort. When we are creating a team we have to apply the same quality as a fine Swiss watchmaker. Craftsmanship comes out of intelligent hard work. I hated practice. I never minimized, however, the importance of repetition in getting ready for a season. Your craftsmanship comes out of your dedication to your practice. Success is a result of consistent practice of winning skills and actions. There is nothing miraculous about the process. There is no luck involved. Amateurs hope, professionals work The three Russell Rules for Craftsmanship are as important to winning as any of the other rules in this book. Let me introduce them to you: RUSSELL RULES Rule One: Learning is a daily experience and a lifetime mission. I truly believe in the saying "We work to become, not to acquire." The more I learned, the more I knew I had to learn. In fact, as part of your daily experience I think it is critical to understand why you are succeeding and build on it. For example, I never watched film of what I did wrong. I always watched films of games where I played well so I could learn more about what I did to help the team win that game. In college, K.C. Jones and I worked on not only being the best in the country, we worked on being as astute as we could possibly be. The basketball court became our classroom, workroom, and laboratory. Whether it was learning how to force a certain shot that would result in a certain rebound angle, or how certain players would likely act in game situations, we wanted to understand the game at a level other players before-and I am not sure since-never approached. Rule Two: Craftsmanship and quality are never an accident. Craftsmanship is the result of sincere effort, principled intentions, intelligent direction, and skillful execution. It could be said that craftsmanship represents the highest choice of many alternatives. Rule Three: Make craftsmanship contagious. Players on great teams learn from each other. The lifetime of experiences we bring to each relationship is a gift to be shared. An entire team working to be the best will be the best. What, precisely, is it in craftsmanship that is so valuable as a leadership skill? Why should doing something well necessarily put you one step ahead of your competitors or allow you to feel that your life is somehow better for it? In my own experience, the answer to those questions goes back to my father. My father once told me that anyone who worked for three dollars an hour owed it to himself to put in four dollars' worth of work so at the end of the day he could look any man in the eye and tell him where to go. My father believed that you could feel a sense of security for giving more than what someone was expecting from you. I took my lead from him. When I received my basketball scholarship to the Universiy of San Francisco, I directly attributed my getting that scholarship to following my father's advice and the understanding I had gained from him about craftsmanship. I rediscovered my father's words about the meaning of work, and I committed myself to learning everything I could to improve my game, to making myself the best basketball player on the planet. At that time, I wasn't much of a shooter, so, with the encouragement of my freshman coach, I spent hours in the gym shooting. Night after night, sometimes until midnight or one o'clock in the morning, I would take up to five hundred shots left-handed and five hundred shots right-handed, mainly hook shots, the kinds of shots a center would take. I'd swoop left and right, touching the ball off the glass or going straight for the basket. It was hard work, but I couldn't get enough of it. As I wrote in "Lesson Four," whether you love practice or not, you need to learn something new every time you go out there or else you won't get positive results. I loved what I was learning, and the payoff was acquiring skills I didn't have before. When I began practicing these skills, I did not feel particularly comfortable going to my right because I was left-handed. But I kept shooting right-handed over and over again until, slowly, I began to have a feel for it. It was like taking piano lessons, when you reach the point where your right hand has to do something different from your left. If you have no real interest in lessons, you might give up at that point or continue in such a way that the skills you acquire will be adequate and no more. But if you love what you're doing, the very difficulty of what you need to do will drive you further, and the sense of accomplishment you gain will mean that much more. Weeks, months, tens of thousands of shots later, I became able to use both hands easily. Because I was a center, I needed to understand how best to move my feet. The small moves a center makes in the post are all about footwork: where your feet are planted, when and how to shift them, how to take small steps rather than big ones, when to turn, what angle your body should take to the basket and to your defender. I wanted to be able to move in such a way that defenders wouldn't be able to outguess me, to either overplay me to my natural hand or drop back because they minimized my ability to score. I also wanted to be a threat whether I shot the ball or not. If I wasn't going to shoot, I wanted to make sure my movements would be more likely to confuse or tie up the guy guarding me, so that I might have better passing options or be in a better position to set a screen or to draw double coverage. I taught myself to have "smart feet" by running and moving, whenever I could, like a guard rather than a big man. Smart feet are the result of both brains and endless work. Craftsmanship is inevitably linked to success, but, even more, it is tied to leadership. The better you are at what you do, the more you set an example without words or memos for others to see and follow. Craftsmanship is infectious because it raises the standard. It is a funny notion, but many times if you refuse to accept anything but the very best, you often get it. In my opinion, craftsmanship needs to become an important part of your business culture. My father used to say, "If you don't do it excellently, don't do it at all." Besides your employees, craftsmanship becomes an important element of your institutional and product brands. I have often believed that anyone can cut prices, but it takes brains and commitment to make a better product. From the perspective of quality, there is as much craftsmanship in a Honda as there is in a Lexus, and because of that craftsmanship both cars are enourmously successful. I was a high jumper in college. I did it just for fun, and I had considerable success at it, but jumping became an integral part of my craft as a basketball player. Because I left my feet so often in defending, much against prevailing opinion and the specific instructions of my coach, I had to teach myself how to do this correctly and effectively. No one could teach me these things because no one was doing it this way. I knew that jumping could be a tremendous asset to me because I had that kind of power in my legs. The technical problem for me was what to do if I went for a fake. If I was up in the air and a player got past me, what, if anything, would enable me to recover? I figured out that the way I landed determined what I would be able to do. If I landed straight-legged, I was lost. And most guys when they went into the air didn't think about the way they came down, they just let their feet guide them back to earth and there they were. But I discovered that if I came down with my legs in a flexed position, nine times out of ten I'd catch the guy who'd gone past me and I'd be waiting for him when he shot again, so he'd wind up saying to himself, "Where did he come from?" I worked on this. I kept practicing jumping and landing in a flexed position. I needed added power and agility for this as well. I devised an exercise for myself where I bounced up and down on my toes because that increased strength in my feet, ankles, and lower legs. I'd do this "bouncing" before practice, jumping and touching the rim thirty-five times. I kept watching other players all the time, always trying to match their moves against what I could see myself doing. I noticed that when players went up into the air to take jump shots, for example, they didn't go as high as they could. Most players set up their jump shots so as to control the shots they could get, which meant that I had a tremendous advantage as a defender because I could go higher, as high as I needed, on my jump. A good shot always comes from the toes and then flows up through the body to the fingertips. And I observed then that for good shooters to get off good shots, they had to be in position to use their feet, their toes. They had to essentially square up to the basket, and if they didn't, if they were forced to turn to the side, for example, they would be less effective. So I taught myself to always move against a shooter in such a way that he would not be able to square up. If I was correctly positioned, I would be able to spring out or to the side so quickly a shooter would wind up altering what he did, taking a more difficult shot even when I had little or no chance of blocking it. In my time, they didn't keep statsitics for blocked shots (that started in 1973-74). But a few years ago, I was talking to Jack Ramsey, the veteran NBA coach who had seen many of my games, and he said he thought that I averaged double-digit blocked shots per game, and that for each of those blocked shots I forced shooters to alter what they were doing five or six times. In high school and college, I read all the articles I could on basketball. I had stacks and stacks of magazines. I studied what players said, learned about their habits and idiosyncracies, and I remembered all of them. I pored over photographs of players, particularly ones whom I thought I might be playing against at some time, or players whom I simply admired, who I believed had something in their game I might be able to use. When I got to the Celtics, I was a different kind of player. I was a center but I had the skills of a guard. I had through all those hours of work made myself into someone who could move in a new way from an old position. I felt my craft as a basketball player was growing. The next stage for me was to bring my craft from my individual success to my team. I knew that Red and my teammates might not immediately see everything in my game. If I were a golfer, my game would have been complete. But I was player in a team sport, and now I had a real team to play with. My experience would be the same as that of someone who was a top salesman and was then promoted to management. I had to shift my focus from becoming the best I could be to making my team the best it could be. I had no idea how much more I still had to learn. I wanted to match my skills to the skills I saw around me. How to do that? How to take advantage of each player on the floor, how to make sure what I was doing would bring out the best in everyone around me? I saw right away how impressive the Celtics' fast break was and how brilliant Bob Cousy was in leading it. My first job, therefore, was figuring out what I could do to trigger the break. That meant devising a way to get Cousy the ball off the backboard as quickly as possible. Sounds easy, but it wasn't. If your big man goes up, gets the ball, comes down with it, plants, moves his arms from side to side to make sure no one is going to steal the ball, there will be no fast break. Or if the center is a little quicker, comes down, turns, looks, throws an outlet pass, that extra second or two consumed will still allow defenders time to get back. Because I had worked so hard on my jumping and because I had strong peripheral vision, I could see on either side of me when I went up for a ball. If Cousy was positioned in one area when I went up for the rebound, I could take the ball off the backboard and pass it to him in the same motion. All I needed from him was the color of a jersey in a familiar area of the floor so that when I made this single movement of jumping, twisting, and passing, I would not be throwing the ball away. Left side, white shirt (on the road, green shirt). I could do this so quickly defenders would often be standing flat-footed watching the play from the backcourt as we completed the break with an easy basket. I got more out of being able to execute that than I did out of awards and public recognition. It was a joy to perform that move perfectly and successfully time and time again. The same was true when it came to running our plays. I prided myself on how much I could do. In the Celtics half-court game, all plays went through me. For them to work, every guy on the floor had to be in motion. Each of us had a part to play, each had to be ready to become a second, third, or fourth shooting option. Our plays required an ongoing, active basketball craftsmanship where the movement of one player would immediately be understood by every other player. My job was to see every move by every player, to coordinate and process it as if my brain were a computer, and then to make the right pass. There are eleven different kinds of passes from the center position: high post pass facing the basket, low post pass with your back to the basket, bounce passes left and right, hook pass left, hook pass right, jump pass, pass behind your back, over-the-shoulder pass, step pass, which changes the passing lane, and lob passes over chasing defenders. I always had to keep in mind who the player was I was passing the ball to, who was defending him, where that defender was positioned. I had to know how different players saw the ball when I made a pass. My teammate Satch Sanders, for example, wore glasses. He was a wonderful player, highly intelligent, and could move well without the ball, so he usually found ways to get himself open. But, when he wore contact lenses, he couldn't see below his waist. So any pass that came to him at his knees or even at thigh level, he would not be able to handle well. The joy I got was that my passes almost always were the right ones, never spectacular, always delivered so that the player on the receiving end would be in a position to do something with it. If I got the ball to a shooter who had only a second of daylight, I made sure I sent a "dead" ball, a pass with a lot of backspin so that as soon as the player caught it, he would be able to get off a shot. I loved making passes in from out of bounds because I could see each of my teammates so distinctly in the rush of bodies moving this way and that. By then, because I had acquired enough technique, I could slow those bodies down in my mind's eye before I released the ball. Playing defense with a real team was an even greater challenge, but had an even more satisfying payoff in terms of seeing how much other teams became intimidated or were thrown off their game. When I came to the Celtics, I believed that it was possible to win games with defense alone. My team made me a prophet in my own time. It's much harder to play defense because you're not handling the ball, and a team has to be even more precisely coordinated in what they do. On offense, it's possible to take a break, to stand around a bit, let other players take over. On defense, if you take a break, a good offensive team will burn you. On the other hand, when you and your teammates are all doing the job-and you're all that good-the great reward is watching the other team slowly suffocate. A really good defensive team uses its intelligence to an extraordinary degree as well as its agility and muscle. Every move you make on defense has a consequence for your teammates. For example, if you see that the player you're guarding wants to go left to shoot, inevitably a defender will try to do something to force him to go the other way. But in doing that, the offense will take note and do something else, and it's up to the defenders to pick up on that. Everyone on defense has to move and make exactly the right counteradjustments for the team game to work. If double-teaming leaves someone open, for example, it is important for the double-team to come together in such a way that the guy with the ball won't be able to see the open man. We perfected that on the Celtics. Each team, each player, is different. On team defense, it is absolutely necessary to know your opponents as well as your teammates. The way they move, they way they pass the ball, the way they move without the ball, are all part of what must be taken into account for the defense to work. On my team, because we were so conscious of team defense, we were especially mindful when we saw good defense thrown at us. The challenge to break it down was great, but the rewards when we were able to do it were oh so sweet. The Knicks in the late 1960s, for example, had one of the best defensive units in the game. In 1969, we faced them in the play-offs after they had taken us six times in seven regular-season games. Before our series against them in the Eastern Divisional Finals started, I took home the statistics from the regular season and studied them. I was aware that the Knicks had done a great job of closing us down, and I wanted to see if anything in the numbers would give me a clue. As a player and a coach, I didn't look at statistics the way sportswriters and fans did. I wasn't interested in who scored most, got the most rebounds or assists. I was after clues that would let me see patterns, what it was that enabled the Knicks to succeed against us. The stats, this time, revealed something startling about the Knicks' defense. I noticed that in each of the regular-season games against them, I had taken no more than five or six shots. Now the guy guarding me and the backbone of the Knicks defense was Willis Reed. Because I hadn't been shooting much, Reed had been free to help out on defense. He had been able to leave me safe in the assumption that I wasn't likely to get the ball and shoot. The Knicks gained from this in the way they used Walt Frazier in tandem with Reed. Frazier, a great player who really never received enough credit, was as good a defensive player as there was. So Frazier, when Willis moved away from me to help out, would go after a likely shooter and drive him toward Reed. Again and again, our best or most likely shooters found themselves stifled or hemmed in. How to defeat that? The answer for the play-offs was clear. Don't give Willis Reed that kind of freedom. To break the defense, I needed to shoot the ball. It was as simple as that. So in the first game of our series, instead of taking five or six shots, I took twenty-three. And we beat the Knicks-in New York-108-100. Reed found himself pinned to me, unable to drift away to help out. Frazier and the rest of the Knick defenders were then unable to keep up with our shooters. The Knicks ran the same defense against us that had been so successful during the regular season, but we had found a way to break it. Teams that play at the skill levels of the NBA constantly adjust and readjust, and the same was true in this series. The Knicks, just because they were so good defensively, soon saw what we were up to and adjusted by rotating defenders to help out Reed so that my scoring would be limited. But as soon as the Knicks did that, we adjusted, too. I now had open men I could get the ball to. In the sixth and final game, the Knicks had adjusted again and we went back to the old pattern, but by then it was too late. The game was over and we won. Team craftsmanship is akin to going from the stage where you are working by yourself on an invention, building a car or a plane, then having to apply what you've learned to the assembly line and to strategies of the marketplace where your craftsmanship has a direct payoff in terms of winning. Craftsmanship can never work by numbers alone, by connecting X's and O's on a chalkboard or by looking at videotape. As a coach, Red Auerbach would seem to an uneducated observer hopelessly out-of-date today. He didn't watch film or video. He didn't scout other teams. He didn't go around measuring body fat with calipers and getting digitalized readings of a player's reaction times and muscle strength. There were no team meetings to inform us what had happened in our opponent's last three games. What Red relied on was his players' skill and passion. He counted on our active ability to think things through and then come up with whatever we needed to do to win. Winning was our assembly line, championships were our automobile. I have no particular attachment to the "good old days," to the automatic assumption that some old-timers make that everything back then was great and everything going on today is lousy. I just believe that Red understood craft. He understood perfectly how the success of a winning team depended on individual skills and team work. Red was a mathematician as well as a basketball man, and he drew on that as a coach. Mathematics allowed him to solve problems, to ask the right questions-even ones that couldn't be answered. It enabled him to see differently. He was forever watching geometric patterns on the floor, picking up the way the flow of the game changed. He was constantly playing with numbers. He was obsessed with what he could do to change the odds of a game in our favor. For example, he'd try to do things early in a game to get us five easy baskets. If we had gotten the five easy baskets, he'd say we had automatically changed the odds because the other team then needed at least five hard baskets to beat us. Five was a number in Red's mind: five baskets, five outstanding plays, five free throws, five anything that would tilt the game in our favor. Red made substitutions according to numbers, too. He wanted patterns of players on the floor at all times, a balance of shooters, rebounders, defenders. If the pattern was broken, the balance was lost, the team was vulnerable. Even in the final minutes of games, the abacus in Red's mind was clicking away: "Okay, we've got three minutes left, we're up by ten, that means if we play good defense and don't throw the ball away, we need three more baskets." Or he'd bark, "They have to score three out of the four times they have the ball, we need to score only one in four." A manager in a fast-moving, highly competitive industry like the retail food industry, for example, faces similar challenges. To stay a step ahead, the manager of a supermarket chain has to juggle inventory, sales prices, warehouse supplies, personnel, down to the wire if he expects to stay that one step ahead. Certain goods that are not available from wholesalers will not become sale items, but others will. Knowing exactly how many items will beat a competitor's price that week, knowing just how much to order so that perishable goods are never backed up, all of these choices carry the pressure of the game's final minutes but also, provided the manager really understands the significance of patterns and odds, a tremendous likelihood of winning. But Red left all of the doing to us. He treated each of us as the individuals we were. Some players he rarely talked to, while other players he took aside and coached. When he left a player alone-such as K.C. Jones or Cousy or me-it was because he knew that the player was doing exactly what he needed to do for himself and the team. When he coached a player-such as Sam Jones-it was never with the sense that he was going to show him skills the player didn't possess but only to support him in using them. For a player to experience the game on a level where he has to use all of himself, where he is, in effect, a problem solver as well as a body, constantly committing himself all out to the possibilities of the moment, creating chances and opportunities for himself and his team, is to experience the game at the highest level of creativi-ty. Craftsmanship at this level is about artistry. The idea that there is one way, a correct way, a one-size-fits-all way to do things is as mistaken as the eye of a video camera that sees everything but not the significance of it. Craftsmanship is a lot like finding your leadership style. There is no one way to get there. Each player has to find within himself what craft is really about, what it is in craftsmanship that is individual and distinguishing. A team player applies all that, and in the applying creates success for his team. A word more about the game I have known so well. One time in Los Angeles during the lockout, I was talking with Shaquille O'Neal, someone I have great respect for as a player and as a person. We got into a conversation about foul shooting. His critics never let him forget how much he hurts his team by not making free throws. I told him by all means to keep working on the craft of foul shooting, but to always keep the focus on what he was doing overall to help his team win games. If he got sidetracked worrying about shooting fouls, it would only undermine what he did best. Shaq is a player who offers far more to his team than his ability, or lack of ability, to convert free throws. He has a complete game to offer. He is a mammoth presence in the middle of the paint. No one can stop him from scoring. If his opposition fouls him again and again, he has the strength to break that strategy eventually. He is a much better passer than people give him credit for. His game is full of possibilities, and all he really needs to remember is to use all of himself and not let himself get sidetracked. The Lakers won a championship in 2000, the first with Shaq in the middle, not because of his foul shooting, but because he found a way to use all his skills to help his team become a winner. Personally, I found a great thrill in using my craft as fully as I could. But it was always about winning. I loved those times when a situation looked absolutely hopeless and yet I could still do something to turn things around. I probably broke up thirty-five to forty three-on-one breaks in my career, for instance. The feeling of joy and accomplishment I felt after each one of those defensive gems was contagious. I wanted to do it again. I remember once that we were a single point down in a regular-season game against Philadelphia with twelve seconds left. Archie Clark of the Sixers had the ball in the frontcourt and was dribbling out the clock. I was the only player near him. I knew I had no chance to take the ball from him. He had so much room he could have just stood still with the ball. So I stared at him-and he stared back at me, smiling. What followed happened so quickly it deadens out in the writing. My mind flashed on this player; I told myself, "Archie Clark is a scorer who is more inclined to take a layup than a jump shot. If he had a shot, he would be more comfortable taking a layup ... so what I'm going to do is turn my back and start to walk off the floor like I've given up." I did this-and he did exactly what I hoped he would do. He drove to the basket for an easy layup. But there I was, waiting for him! I blocked the ball, called time-out. There were three seconds left. We took the ball out in frontcourt. Havlicek passed in to me down low; I dunked. We won in regulation. There's an old saw about doing your job and letting go of the results. It's grounded in deep truth. I was always more interested in the doing, in the craft of playing, than I ever was in rings on my fingers. At the height of my game, what I found was the joy of my life. I remember one time in a game when I felt Icould do no wrong and everyone else on the court-on both teams-was playing equally as well as I was. This went on for five, maybe six uninterrupted minutes before the referee finally blew his whistle and called a foul on the other team. I was furious! My teammates looked at me as if I were nuts. But all I could think of was that this beautiful plateau of accomplishment, flight at another almost perfect level, had been interrupted. I had almost forgotten that that whistle meant a couple of extra points for the Boston Celtics. Craftsmanship, of course, applies in all situations, whether people belong to a team or are working for themselves. Hal Dejulio, who recruited me to USF, was a great insurance salesman. I asked him "How do you sell so much insurance?" "I don't sell insurance," he answered, "I help people buy it." Craftsmanship is a way in to what's best in yourself. The real mastery is always of yourself. Parents, for example, say they love their kids. But parents who really care are always looking for ways to make their children's lives better, to strengthen the family unit they all belong to. The art of parenting means that you reach beyond just saying to yourself that you love your kids. You need to find what it is in yourself that allows that to happen. How do you show your love for your children? How do you build your family into a model that works? When I was a single parent, having to raise a twelve-year-old girl, I had left my job with the Seattle SuperSonics. My friends expected me to pack up and leave Mercer Island and the state of Washington. I had no intention of doing that. My daughter was in one of the best public schools in the country. She had a real and ongoing life of her own. There was no thought of moving. And it wasn't a sacrifice. I wasn't about to visit my troubles-that I was out of a job-on my daughter. My "craft" in parenting meant recognizing that and acting accordingly. My job was to establish a routine, everyday life between us that would allow her to feel safe and comfortable. You share your life with your children, you provide for them, you allow them to be who they are while, at the same time, offering them guidance and protection. It's the most delicate-and rewarding-of arts because it is about love. It goes back to that old saying that it's not what you give but what you share. So, in summary, let's look back at a few pertinent Russell Rules for Craftsmanship: RUSSELL RULES Rule One: Learning should be a daily experience and a lifetime mission. Michelangelo said, "I have offended God and mankind because my work didn't reach the quality it should have." I always believed if Michelangelo felt that way, then I would always strive for the best because anything else would not be enough. Rule Two: Craftsmanship and quality are never accidents. In lesson three, on listening, I talked about the importance of careful language selection to get folks to listen more effectively. Well, think about replacing the word quality with craftsmanship and reintroduce it as an integral part of your brand. Rule Three: Make craftsmanship contagious. Craftsmanship and teamwork go hand in hand; one cannot happen without the other. If others see the care and dedication that you put into your job and into winning, they will follow. Accomplishing that is a true mark of a winning leader. One final thought. Because I have gotten so much joy from the things I have done in my life, it has sometimes been hard to think that joy itself is a leadership quality. But it is. When a leader is obviously passionate and joyful in what he or she does, that is inevitably communicated. It sets a tone, a standard in which winning is not the only thing but the most natural thing in the world. —From Russell Rules : 11 Lessons on Leadership from the Twentieth Century's Greatest Winner, by Bill Russell, David Falkner (Contributor). ©May 7, 2001, Penguin USA used by permission.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

All prices subject to change and given in U.S. Dollars. |

All materials contained in http://www.LeadershipNow.com are protected by copyright and trademark laws and may not be used for any purpose whatsoever other than private, non-commercial viewing purposes. Derivative works and other unauthorized copying or use of stills, video footage, text or graphics is expressly prohibited. LeadershipNow is a trademark of M2 Communications, LLC. |