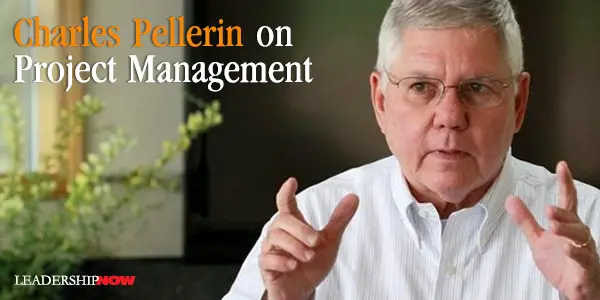

Charles Pellerin on Project Management

APPRECIATIVE INTELLIGENCE—the ability to perceive the positive inherent generative potential within the present—is an important component to develop as part of organizational culture. AI contributes to a high incidence of innovation and creativity and the potential development of previously unnoticed strengths in people. This happens by the actions of leaders at all levels, to encourage people to look at everyday issues—the commonplace—in a new way; by telling a new story.

Former Director of Astrophysics for NASA, Charles Pellerin believes that most projects fail around social and leadership issues. Both "unknown and unnamed" social undercurrents are at the root of many, if not most, project difficulties. NASA publication,

ASK Magazine talked to him about project management and how social and leadership issues come to play in why projects fail. Here are some excerpts from that interview:

Can you explain what you mean by "social issues," and how they relate to leadership?

I began to see a pattern repeated far too often when a successful project manager would get promoted or leave a project for some reason. I would replace him with someone who looked just as good on paper, but three months later, all of a sudden, the project started to fall apart. Milestones got missed. Reserves depleted too fast.

I was frustrated that I couldn't anticipate and recognize the difference between project managers who were going to succeed and project managers who were doomed to fail. We could predict things like sensor performance. We could understand the detectors. We could understand the power systems. But we couldn't understand this one critical, invisible piece: What makes a good manager?

Was it the magnitude of the Hubble telescope problems, launching it with a flawed mirror, which brought this all to a head?

Yes, exactly. If you go back to what was happening at the time, we launched Hubble in 1990 and very soon thereafter we found that a technical person had made an error. At first we thought, "Now at least we know what the error was. We can figure out how to fix it." And that's just what we did -- we fixed it. This would appear to be a very happy story for me; I got a NASA medal for the repair mission.

That's all well and good, but then I said, "Wait a minute. We should have had systems in place to find this kind of thing." The procedures are written. The engineers sign them. Safety & Quality Assurance stamps it all to verify that this is being done properly along the way.

Hubble was the final straw for me. I needed to understand what had happened, because when I looked around me I realized it was commonplace. I mean, take a look at Challenger. It was not, in a sense, a technical failure. It was another human communications failure. I knew a bunch of those people. They were damn good managers and engineers, but they got caught in a story. They created an environment where it wasn't safe to tell the truth.

That's interesting how you describe it as people who got "caught in a story." How do stories figure into this leadership quotient?

The stories that you carry affect how you make decisions in your life. That's why I'm very interested in the stories we tell. We all perceive reality through the filter of the "stories" we believe. We create stories to make sense of our experience. And, we act within this context as if it were truth, because to each of us it feels like truth.

You said that leadership was at the core of the Hubble mishap. Do you find evidence of this in other projects?

Sure. Diane Vaughn, in her book The Challenger Launch Decision, said she was a year into her study before she realized that then-accepted accounts of what happened were wrong. Vaughn concluded that the disaster was caused by an "incremental descent into poor judgment." And she went on to say that the technical risks grew out of social issues. Notice the word "social" again. She realized that signals of potential danger had been repeatedly "normalized." That was okay in the context of the stories their culture supported.

This would help to explain the recent experiment reported in the Washington Post by Gene Weingarten to discover if violinist Josh Bell—and his Stradivarius—could stop busy commuters in their tracks. Surprisingly, he did not. If our story is to ignore street musicians and includes the belief that no famous musician would ever do it, then we will ignore street musicians and we will not scan the streets looking for our favorite artists. (If you haven’t read it yet, do so. It’s a great story.)

Pellerin has been developing since his retirement from NASA in 1995, a leadership/culture assessment and learning system called "Four-Dimensional (4-D) Leadership." He states, “We began with workshops, and then added coaching, and now have Web-based diagnostics customized for NASA projects. Simply put, we make three measurements in each of the social dimensions -- directing, visioning, relating and valuing—that we believe are fundamental to effective leadership and efficient cultures.

“I truly believe that we can identify and address the root cause of most project difficulties. That's my story. And many of the projects I'm working with are choosing to run that story as well -- because they see results. You know, no story is "good" or "bad." Some just get you the results you want and some don't.”

* * *

Like us on

Instagram and

Facebook for additional leadership and personal development ideas.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 07:21 AM

Permalink

| Comments (0)

| This post is about Creativity & Innovation

, Problem Solving

, Thinking