|

|

11.02.10

Political Leadership and Compromise

ON ELECTION DAY our minds turn to political leadership. Men and women are elected with the expectation that they will honor commitments they have made to the voters. This often leads politicians to take a short-term view of almost everything. At the same time, plagued by reality, a politician (or any leader for that matter) may find that they have to change direction or offer a compromise. This leads to the “disconnect” we frequently have with political leaders. The problem facing politicians is that reality doesn’t sell. (And of course, we play a hand in that.) So frequently, what gets them into office is not the approach that will get the job done. It is a dilemma all leaders face. It’s a dilemma that requires a certain degree of wisdom. Prudent flexibility, adaptability, and compromise are necessary qualities for leadership. Yet we often hold in high esteem leaders who don’t back down more than those that compromise their position. No one wants to be viewed as weak. But a leader that will not change or even listen to the need for change can cause irreparable damage. It’s easy to get lulled into a sense of our own permanence. We must remember that leadership is temporary. It is a sacred trust that we hold for only a short time. The skill is in understanding what one can be flexible about and what one should not. We should never compromise principles, but approaches (even the proper understanding of how those principles are applied) may need to be adapted. Values and approaches are distinct from universal laws and principles and are derived from them. The former may change; the latter never does. The fact too remains, that we may be wrong, our perceptions might be faulty and our assumptions may be without foundation. When faced with the facts, we need to be able to change direction and chart a new course without losing sight of the ultimate goals. Stefan Stern recently wrote in an excellent post on knowing when to shift your position: “If you are heading full speed ahead for the rocks it is time to change direction….Good leaders adapt to changed circumstances, and admit it when they have made a mistake.” In the introduction to Profiles in Leadership—an excellent collection of essays on leadership—biographer Walter Isaacson shares a historical perspective on compromise: The greatest challenge of leadership is to know when to be flexible and pragmatic, on the one hand, and when it is, instead, a moment to stand firm on principle and clarity of vision. Even the best leaders get this wrong sometimes. I learned this when writing a biography of Franklin. His instinct was to try to balance the conflicting values that were at issue during moments of tough debate and to find common ground. At the Constitutional Convention, he was, at eighty-one, the elder statesman. During that hot summer of 1787, the rivalry between the big and little states almost tore the convention apart over whether the legislative branch should be proportioned by population or with equal votes per state. Finally, Franklin rose to make a motion on behalf of a compromise that would have a House proportioned by population and a Senate with equal votes per state. “When the table is to be made, and the edges of the planks do not fit, the artist takes little from both, and makes a good joint,” he said. “In like manner here, both sides must part with some of their demands.” His point was crucial for understanding the art of true political leadership: Compromisers may not make great heroes, but they do make great democracies.  FDR on the other hand was not as well regarded and was mostly known for his connections and family background. “In the end, however,” writes Brinkley, “Herbert Hoover left the white house thoroughly discredited, repudiated, even hated, while Franklin Roosevelt was revered by much of the world when he died in office.” The difference was flexibility. Hoover was “A victim of his convictions, convictions that seemed to him close to absolute….Hoover’s unshakable principles shackled him time and again in his effort to deal with the Depression.” On the other hand, the quality that separated Roosevelt “most decisively from Hoover, was his pragmatic, experimental nature.” The contrast between Hoover and Roosevelt, Brinkley concludes, “suggests that leadership cannot succeed through ideals and strong convictions alone. The world is a complicated and ever-changing place, and a great leader must be capable of adapting to change and understanding the diversity of the ideas and principles that shape history.” Roosevelt was more successful in guiding the United States through the two greatest crises of the twentieth century, “in part because his values were appropriate to his time but also because he understood that values must reflect the realities of his age.”

Posted by Michael McKinney at 10:21 AM

|

BUILD YOUR KNOWLEDGE

How to Do Your Start-Up Right STRAIGHT TALK FOR START-UPS

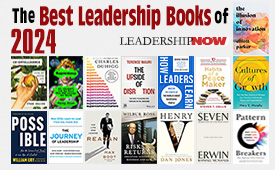

Grow Your Leadership Skills NEW AND UPCOMING LEADERSHIP BOOKS

Leadership Minute BITE-SIZE CONCEPTS YOU CAN CHEW ON

Classic Leadership Books BOOKS TO READ BEFORE YOU LEAD |