|

|

08.27.13

The Art and Science of Perfect Timing

WE SAY timing is everything. And it is. But most of the time it just seems like good luck. In When, Stuart Albert says that using the right tools we can become better at managing and deciding issues of timing. Good timing is a skill that can be acquired. We miss timing issues “because the way we describe the world and the tasks we must accomplish omit the kinds of facts we need….They fail to include all the sequences, rates, shapes, punctuation marks, intervals, leads, lags, overlaps, and other time-related characteristics that are part of the temporal structure of everything that happens, every action that is taken, every plan that is implemented.” And we routinely omit them from our thinking. I had never thought of it that way. I was intrigued. If we don’t look for and note time-relevant characteristics like sequences, rates, duration, beginnings, and endings, we won’t have the information we need to make good timing decisions. For example, we question whether or not the incentives we have chosen are the right ones, but we don’t consider why those incentives became important at that particular time. Albert likens the structure of timing analysis to the structure of a musical score. There is a horizontal and a vertical dimension to it. Five horizontal—sequence, punctuation, interval, rate, and shape—and there is a vertical dimension—polyphony. The way they come together in an organization gives us insight into timing. These patterns form the temporal architecture. Sequence refers to the order of events, like the notes in a melody.

We have to learn how to listen for the rhythm of what is going on, for its moments of tension or release, for moments when we must pause and change direction. Learning to view events in this manner will help us to spot opportunities first, execute on them well, and avoid costly mistakes. The worst timing mistakes are not those that have significant human or financial costs, but those that appear to be inexplicable, where we ask, “How could someone have made a mistake like that?” One example of a sequence issue is Cooper Union’s decision to build a 166 million dollar engineering building on its campus in New York with the hope that a donor would step forward to fund the building. As of May 2013, nobody has. This is a classic sequence inversion error, playing notes out of order—in effect putting the cart before the horse. The first step should have been to attract the donor, who would help select the architect, and then become involved in the design of the building. In order to get the timing right Albert says we need to move beyond spheres and networks, boxes and arrows, trees and branches, and instead think in terms of a tall polyphonic musical score in which a large number of processes and events are playing at the same time. Here’s more:

When provides a more insightful way to look at events and the seven essential steps in a timing analysis. Timing issues are not always obvious but Albert helps us to know where to look and what to look for so we will be much more likely to get the timing right.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 01:37 AM

|

BUILD YOUR KNOWLEDGE

How to Do Your Start-Up Right STRAIGHT TALK FOR START-UPS

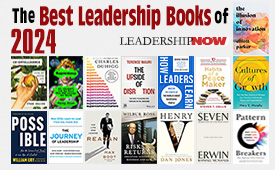

Grow Your Leadership Skills NEW AND UPCOMING LEADERSHIP BOOKS

Leadership Minute BITE-SIZE CONCEPTS YOU CAN CHEW ON

Classic Leadership Books BOOKS TO READ BEFORE YOU LEAD |