|

|

03.05.25

Collaborative Design Thinking in Action: How to Achieve Breakthrough Outcomes

A team approach to problem-solving, informed by the process of design thinking, can be optimally effective in triggering inspiration, leading to fresh ideas that are highly responsive to stakeholders. Indeed, collaboration can be a force multiplier in an effort to reach an intended objective. However, what seems to be missing is how team members can perform successfully and work as a collaborative entity for the good of the project. Collaborative design thinking suggests a customized framework for team members and stakeholders to work together so that the process is unique and relevant for a particular challenge and the individuals involved. A project leader can adjust the design thinking approach to the required matrix of specialties, personalities, tasks, and circumstances — and determine how and when collaboration occurs — to yield the best possible outcome. The following three summary examples include distinctive challenges. The process for arriving at an optimal solution, however, applies to many types of problems in many types of organizations. In each of these instances, the team was able to use an aspect of collaborative design thinking to ask the questions that needed to be asked and achieve breakthrough outcomes. Example 1: Empathy as a Means to Innovate in a Pharmaceutical Company Empathy — a key component of design thinking — helped this team develop a fresh mindset and a full appreciation for special needs, leading to a new way of thinking and, ultimately, to an innovative product. Developing meaningful empathy for stakeholders is a remarkable tool for problem definition and, ultimately, solutions. The better we can get to know the people who will be using the spaces, solutions, or, in this case, products that we design, the better problem solvers we can become. It’s a simple, commonsense idea that is surprisingly neglected. In this case, one team member assumed the role of stakeholder advocate, serving as a proxy for a typical product user. Armed with primary empathic data, she was then able to propose a wonderful, responsive, economical solution that the user could not have imagined. The project was denture adhesives for small sections, or “partials,” that replaced one or two missing teeth. The biggest problem for consumers was that their appliances didn’t fit properly, and would wobble and put stress on their teeth. Food particles would lodge beneath them, causing irritation. That was the initial problem definition from a consumer-need perspective, and also what the team was focused on solving from R & D and marketing standpoints. At a team meeting, one member held a jerry-rigged gardening glove — a simulation of what the consumers were going through. She said, “I’ve been listening to you talk about the consumers, and I’ve been thinking about their challenges. What you’re missing is that you’re not hearing them say, ‘It’s really hard to apply this!’” When they (accidentally) over-applied the adhesives, it was difficult to clean up; the adhesive was essentially a polymer mixed in oil, so consumers would end up with excess oil in their mouths. She also pointed out that the team was perhaps failing to address the right problem, which was over-applying the product. The adhesives are very viscous products that are squeezed out of a tube. They are much more difficult for this consumer group to squeeze than toothpaste—and she wanted the team to understand that. Back to the gardening glove. The member attached bits of hard plastic to the fingers on the glove to provide resistance, so it required more effort than usual when squeezing or doing any sort of motion — mimicking an arthritic hand and giving the R & D team an empathic sense of the experience of the typical consumer. While using the glove, it was very hard to properly apply the new products the team was trying to develop: they were all too thick. One solution was to rethink the original tube design and develop a novel application device. Similar to a pen clicking, a click would provide a metered dose, which was easier on the arthritic hand and did not require a squeezing force. With the glove on, it was much easier to click on the prototype device than it was to squeeze from a tube. Here, empathy provided the means to transcend a given problem, formulating questions that expand, illuminate, or otherwise open up the problem. Example 2: Improving Outpatient Services in a Health Care Clinic Recently, a team investigated how they might improve outpatient services for the family medicine clinic at a major urban hospital center. This is one of the busiest single-site clinics in the country, with over 80,000 patients per year. The team initiated a design workshop with the clinic’s providers to fully understand their challenges. One issue is the late patient who shows up 15 minutes after a scheduled appointment and the resulting stress on the provider, who still has to see that patient and then be late for other patients for the rest of the day. Business as usual — a slip of paper with the scheduled follow-up appointment and a phone call reminder to the patient — was clearly ineffective. The team thought about ways to assist patients to arrive on time for their appointments. They interviewed patients and providers, then prototyped and mocked up potential solutions. They used a storyboard technique to propose an app that would message patients at different times before their appointments, reminding them to show up on time. The team did not create anything brand new; there are existing platforms that accomplish the same thing. However, from the interviews with patients and from a review and analysis of precedents, they were able to ascertain that there are optimal times for reminder texts to be effective and to not be perceived as an annoyance. The team succeeded in proposing a solution that could be immediately implemented in the family medicine clinic, with a simple messaging app for the 90% of patients who had smartphones that could receive text messages. Example 3: Applying Collaborative Design Thinking to Find New Treatment Pathways for Disease Inspiration can come from just about anywhere — even from unrelated disciplines that enable us to examine problems from a fresh perspective. In this case, it was parents, not researchers, who recognized that cannabidiol (CBD) was effective in treating rare pediatric seizure disorders that were unresponsive to mainstream therapies. Investigators, regulators, and physicians took their cue from parents and brought Epidiolex to market. Reframing the question is another tactic in collaborative design thinking that facilitates new ways of examining a problem. Instead of asking, “Is there another, creative way of effectively destroying or removing cancer cells?” we might ask, “What if there is a different, perhaps better, means to achieve remission in a given case?” Articulating questions can be extremely valuable in determining whether or not they lead in a fruitful direction. Posing the right questions is a component in the design thinking loop that can be weighted heavily in the process to provoke a creative response. The innovative response to the “what if” question above involves a promising approach to transform the cancer cells rather than destroy them. Be mindful to pose questions that may be counterintuitive or completely off the wall to elicit the most potentially innovative responses. Obviously, specific and investigational treatment plans are far more complicated and individualized than suggested here, but the point is to demonstrate how bold new ideas can evolve from a different way of thinking. Closing the Gaps Not just for designers and architects, collaborative design thinking can be applied across many disciplines to solve real-world problems and reconcile dilemmas. Design thinking can infuse collaboration with a disciplined way of working; it can close many of the gaps in typically unfocused, occasional brainstorming sessions and attempts at collaboration that ultimately don’t work. While there is no magic formula, components of both collaboration and design thinking can be studied, systematically characterized, and rationally wedded to a process that yields effective and innovative solutions.

Posted by Michael McKinney at 09:56 AM

|

BUILD YOUR KNOWLEDGE

How to Do Your Start-Up Right STRAIGHT TALK FOR START-UPS

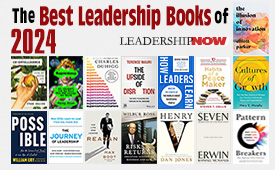

Grow Your Leadership Skills NEW AND UPCOMING LEADERSHIP BOOKS

Leadership Minute BITE-SIZE CONCEPTS YOU CAN CHEW ON

Classic Leadership Books BOOKS TO READ BEFORE YOU LEAD |